Regional Organic Overview

January 1, 2018 | 9 min to read

North America's organic produce sector is experiencing a remarkable surge in demand as more consumers across the Midwest and South embrace organic options. Originally concentrated in coastal regions, organic purchasing has risen nationwide, evidenced by a Nielsen survey revealing that 82 percent of households bought organic in 2016. Retailers, like Food City, are responding by expanding organic selections and emphasizing freshness. Despite challenges such as weather variability and pricing, the organic market, bolstered by Millennial interests, is poised for long-term growth.

Originally printed in the January 2018 issue of Produce Business.

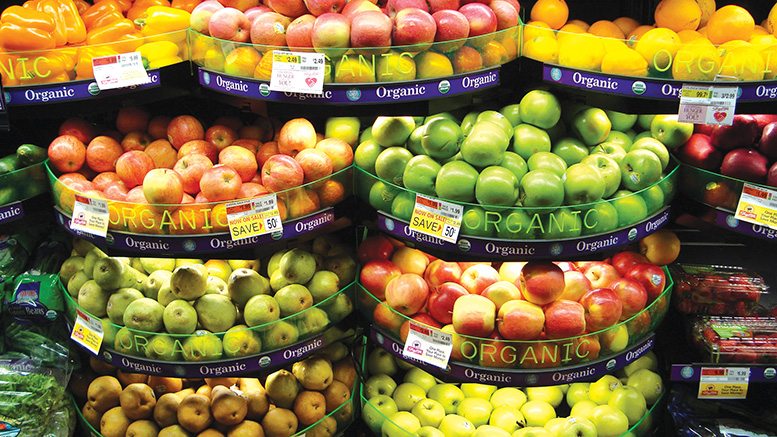

North America’s organic produce industry is thriving as consumer demand increases.

When Ben Johnson, president of Bridges Organic Produce in Portland, OR, got his start in the produce industry in 1992, the embrace of organically grown fruits and vegetables was geographically narrow. “It used to be California, the Northwest, New England, and a little spot in Colorado and a little spot in Minnesota,” says Johnson. “We used to call it the ‘true green’ demographic that was most deeply committed to considering the environmental impact of each purchase. But the Midwest and South have definitely seen a lot of growth in organic demand. The growth has been just phenomenal compared to what we were doing in ’92. They’re really catching up with the organic movement.”

When Ben Johnson, president of Bridges Organic Produce in Portland, OR, got his start in the produce industry in 1992, the embrace of organically grown fruits and vegetables was geographically narrow. “It used to be California, the Northwest, New England, and a little spot in Colorado and a little spot in Minnesota,” says Johnson. “We used to call it the ‘true green’ demographic that was most deeply committed to considering the environmental impact of each purchase. But the Midwest and South have definitely seen a lot of growth in organic demand. The growth has been just phenomenal compared to what we were doing in ’92. They’re really catching up with the organic movement.”

A Nielsen survey of 100,000 households across the United States (Hawaii and Alaska weren’t included) confirms consumer demand for all things organic has spread from the coasts and academic communities into the Heartland. The findings, released by Washington, D.C.-based Organic Trade Association (OTA), showed 82 percent surveyed said they regularly purchased organic products in 2016, a 3.4 percent increase from 2015. Although those purchases included all things organic, fruits and vegetables account for more than 36 percent of all organic sales in the United States, according to Angela Jagiello, associate director of product development for the OTA. “While OTA does not track regional figures, it is safe to say that produce has played an exceptionally large role in the mainstreaming of U.S. organic products,” says Jagiello.

Keith Cox, produce category manager for Abingdon, VA-based K-VA-T Food Stores, the parent company of the Food City chain, can vouch for the sales growth of organic produce in Kentucky, Virginia, Tennessee and Georgia, where the firm’s stores are located. “It is one of our faster-growing categories,” he says. “Organics represent about 4 percent of our total produce sales. I can remember a few short years ago when it was 1 percent.”

Within Food City’s geographic footprint, Cox says Chattanooga, TN, and Knoxville, TN, contribute the largest percentage of organic sales. “There’s a little different buying pattern down there than in eastern Kentucky and southwest Virginia.”

But the good news for the organic produce industry is that, according to New York-based Nielsen, even the states with fewer households purchasing organic products saw double-digit growth in 2016. South Dakota, which at 69 percent was the state with the lowest percentage of households reporting organic purchases, was up 10 percent from 2015.

As with Johnson’s earlier years in the organic produce business, the “true green” Northwest still reigns, with 92 percent of Washington households and 91 percent of households in Oregon buying organic. Today, Johnson heads the company he founded in 2002, and as a grower’s agent and marketer, Bridges Organic Produce distributes throughout the United States and Canada.

Meanwhile, just down the coast in California, 90 percent of households routinely buy organics, and perhaps nowhere more passionately than in Northern California.

“The Bay Area is very unique in terms of the marketplace here,” says Drew Knobel, director of sales and marketing for Earl’s Organic Produce, which carries more than 475 items at its home on the San Francisco Wholesale Produce Market. “Healthy living is key. We have seen quite an increase in organics here. Earl’s year-to-date is up a little more than 26 percent (2017 versus 2016). We saw some months where we grew between 30 and 40 percent.”

“While OTA does not track regional figures, it is safe to say that produce has played an exceptionally large role in the mainstreaming of U.S. organic products. ”

— Angela Jagiello, Organic Trade Association

The company, founded in 1988 by Earl Herrick, who is still at its helm, distributes throughout Northern California — predominately to independent retailers, co-ops and smaller grocers.

“Independent stores and retailers are using it (organic produce) to differentiate themselves from the larger players, like Costco and Whole Foods. They’re nimble and able to make decisions quickly,” says Knobel.

Knobel cites Oliver’s Markets, an independent, employee-owned chain of four stores in Sonoma County, CA, as an example. Knobel collaborated with Michael Peterson, produce coordinator for Oliver’s, on an experiment at the chain’s flagship store in Cotati, CA. “That store historically got up to a 40 (organic)-60 conventional split,” Peterson says. “A couple of years ago, we started talking about putting organics up front. We made that flip, and called it out to our customers to let them know. You know how important it is to have a regular routine when you go to the store. After we did the switch, our sales flipped to a 60 (organic)-40 store. For the most part, our customers were very happy with it. It went over very well.”

Oliver’s Market celebrates its 30th anniversary in 2018, and Peterson has been there for 18 of them. “In that time span we’ve definitely seen our customer preference go to organics,” he says. “Our customers pretty much tell us what they want in the store, and over the years they said they want more and more organic.”

As larger chains adapt to the growing appetite for organics, retailers such as Food City are making more room for organic fruits and vegetables. “The space we’ve devoted to organics has grown,” says Cox. “I can’t give you a percentage, but to give you an idea, within the past three years we’ve added a misting vegetable section that we didn’t have before. Since we’ve added those, it’s helped the vegetable part of the category. We have a dry packaged section for non-misting items. In an average store we’ve got 48 linear feet of organics, but some stores have as much as 60 feet.”

Organic Canada

As U.S. consumers increasingly make organic food choices, so do their counterparts in Canada, the fifth largest organic market in the world, according to the Canada Organic Trade Association (COTA) in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

As U.S. consumers increasingly make organic food choices, so do their counterparts in Canada, the fifth largest organic market in the world, according to the Canada Organic Trade Association (COTA) in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

“The Canadian organic industry is thriving with double-digit growth rates over the past decade, and there are no signs of slowing down,” says COTA in its 2017 State of Organics report issued in July 2017. “More than 55 percent of Canadian consumers purchase organic products on a weekly basis, and more than 80 percent of these consumers have maintained or increased their organic purchases in the past year. The sector was estimated to be worth $4.7 billion dollars in 2015, up from $3.5 billion in 2013, representing $1 billion dollars in growth in just two years.”

“I believe Canada is eating more fresh produce per capita than the United States,” says Bridges Organic Produce’s Johnson. “With a smaller population, they’re going through a lot of fruits and vegetables.”

Pricing Produce

In the United States, the cost of organic produce is frequently cited as a deterrent to a higher consumption of fruits and vegetables. But experts say that is changing.

“Price is far and away the largest barrier to purchase when it comes to organic,” says OTA’s Jagiello. “However, we have seen some data indicating that the gaps are decreasing in a number of important categories. Price-conscious families are becoming increasingly savvy to options for extending their produce dollars, including purchasing in-season and shopping their local farmers’ markets.”

The OTA’s 2016 Produce Deep Dive report, with data from Nielsen Fresh, reported that gap had decreased by approximately 8 percent since 2011.

Cox sees the divide narrowing at Food City supermarkets. “The costs have come down on organics, and they’re getting more and more in line with conventional produce. That’s the reason our share of units is getting larger.”

Earl’s Organic Produce’s Knobel agrees. “The prices overall are getting a lot closer as supply increases,” says Knobel. “But I think most people will trade up for knowing where their food is coming from, and knowing it’s healthier for them.”

Within Reach

Another change driving organic produce consumption across the country, according to industry experts, is increased availability across the retail landscape.

“As retailers double-down on organic, shoppers are finding an increasing variety of organic produce at all manner of retail outlets, from club stores to their local co-ops,” says Jagiello.

Bridges’ Johnson agrees. “Certainly, Costco is selling a lot more organics than ever before. The various Kroger banners are as well. I think the chains have realized the organic consumer is a desirable consumer to bring into their stores, so they’re really seeking that customer.”

But, according to Johnson, the growing number of retailers selling organic produce presents other challenges. “It feels like the competition among retailers is really becoming intense, and everybody’s trying to carve out their space. There are many new stores, and a lot of stores carrying a lot more organic. It used to be there was a real black-and-white divide; natural foods stores had organic, big supermarkets didn’t. It’s more gray now. There’s a lot of competition. It’s driven everyone to be more aggressive and tighten up their operations. Because competition is intense, margins are tighter, and people are having to drive for more efficiency as a way to compete more effectively.”

Organic Challenges

Challenges shadow growth, and the organic sector is facing its own.

“Weed control and labor issues,” says Jagiello. “A huge problem in Florida that citrus growers (organic and conventional) continue to struggle with is the devastating effects of Citrus Greening Disease. The OTA’s Organic Center — a non-profit founded in 2002 with the mission of convening and conducting credible, evidence-based science on the environmental and health benefits of organic food and farming, and communicating them to the public — is working with researchers from the University of Florida in Gainesville to identify solutions for combating this massive threat to the citrus industry.

“There are also concerns about the continuation of NAFTA; the sector is closely watching Mexico’s new organic standards,” she continues. “Finally, there’s continuing discussion and debate over production/standards development for container and greenhouse production.”

Although weather has always played a pivotal role in the supply and quality of fruits and vegetables, drastic changes in weather patterns concern many growers, distributors and suppliers.

“The frequency and intensity of weather events is increasing, whether it be heat waves in the Northwest, which have affected berries, cherries and apples, or hurricanes in the Southeast,” Johnson says. “There are many more climactic challenges than we used to see, and increasing risks.”

“Everything’s based on weather in this business,” says Food City’s Cox. “It doesn’t matter whether it’s conventional or organic. We didn’t have a good 2017 on organic salad, just because of weather-related issues. We weren’t able to do as many ads as we did in 2016. Our units are down, but our sales are actually up just a smidgen. Nothing to shake the world up.”

Johnson adds supply and demand into the mix. “In general, we’ve been through a period of years where demand exceeded supply, and I feel like on many crops that is starting to tilt the other way,” he says. “We’re seeing lots of product moving, but the dollars are pretty flat. So we’re moving more boxes, working harder for the same amount of money. The questions then become, at what pricing level is organic sustainable and worthwhile for the growers, and at which point do they start to veer back the other way? And at what point does the demand catch up with supply so we’re back in balance?”

Jagiello says supply and demand is an issue for all of agriculture. “It’s not unique to organic. The forces of nature create ongoing cycles of bounty and scarcity. As we see more extreme weather patterns, this will likely only increase.”

And yet, as nature and other forces present obstacles, there are many reasons for optimism about the growth of organic produce sales in all regions of the country, including the 123 percent increase in dollar sales of organic fruit from 2011 to 2016, and the 92 percent increase for organic vegetables, as reported in the OTA’s 2016 Produce Deep Dive report.

“When I think about all the challenges ahead, the one thing that I keep reminding myself of is that I think Americans are shifting to more fresh produce and away from meat and processed foods,” says Johnson. “And every small, incremental change in that means a lot more produce business. If people would actually eat five to nine servings of fruits and vegetables a day, we couldn’t even begin to keep up with the demand. I feel the younger generations are rapidly shifting in that direction. I think that’s going to be good for the business long-term.

Fermenting Growth

Organic produce experts say consumers are eating their daily allotment of fruits and vegetables in increasingly creative and innovative ways, adding new sales opportunities for retailers.

“The biggest increase that I see now — and see even getting bigger — is the organic juice category,” says Keith Cox, produce category manager for K-VA-T Food Stores, headquartered in Abingdon, VA. “We actually picked up a new line — an organic kombucha — that has done extremely well. We have tried some other types of organic juice in the past that didn’t do very well at all.”

Angela Jagiello, associate director of product development for the Organic Trade Association (OTA), Washington, D.C., says, “Fermented items are popular, including vegetables and beverages. A great example of an organic innovator in the space is Farmhouse Culture, Watsonville, CA (which makes probiotic-rich, gut-healthy foods, including fermented kraut). Also, value-added items continue to proliferate — from pre-packed vegetable meal starter kits including stir fries, to ready-to-cook vegetables dices, rices, noodles and fries.”

Millenial Power

Millennials, credited with the push for more knowledge about the food they eat, are widely predicted to help fuel growth within the organic sector.

Millennials, credited with the push for more knowledge about the food they eat, are widely predicted to help fuel growth within the organic sector.

“OTA research has consistently shown that organic becomes more important to shoppers when they have children,” says Jagiello. “While 25 percent of Millennials are currently parents, that figure is expected to climb to 80 percent in the next 10 to 15 years. It’s a potential game-changer for organic.”

K-VA-T’s Cox also cites Baby Boomers as an important demographic among Food City organic produce shoppers. “They’re over 50, and paying more attention than the 30- and 40-somethings. Most of them are well educated, and they’re looking at their retirement years and want to live a long time. They’re making better eating choices than they did 20 years ago. And they’re also the ones who have the most money.”

Knobel also gives Boomers a nod. “I think Millennials are a factor, but no different from the Boomers. I think the Boomers have more money than the Millennials. And they definitely have a health component to their decision-making as well.”

17 of 20 article in Produce Business January 2018